A Very Personal History of Wyatt Technology

Written by Geofrey Wyatt

Part 1: The Early Years

Part 1

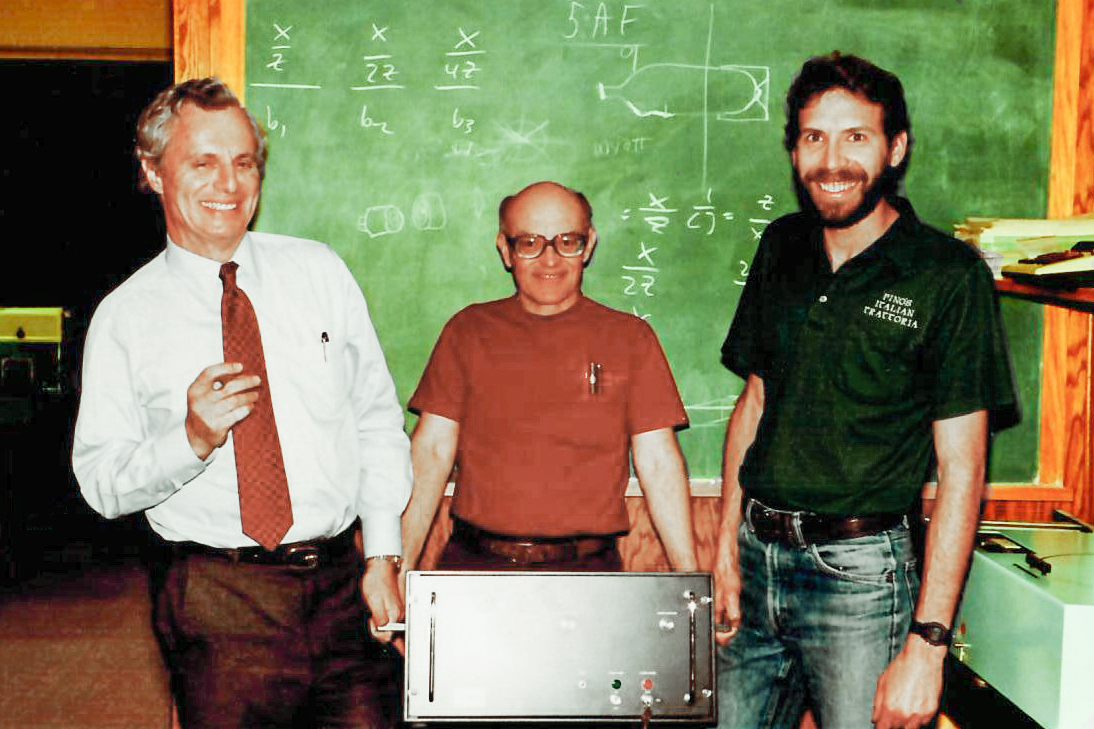

It’s hard to believe that Wyatt Technology began its improbable life forty years ago. Many of our employees and customers weren’t even born then! At the time, Dr. Philip Wyatt was a lecturer in Physics at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He had closed his first entrepreneurial venture, Science Spectrum, in the summer of 1981. But by a stroke of good—if delayed—luck, a proposal he had sent to the US Army in 1981 was awarded a contract in early 1982. And Wyatt Technology Corporation (WTC) was born.

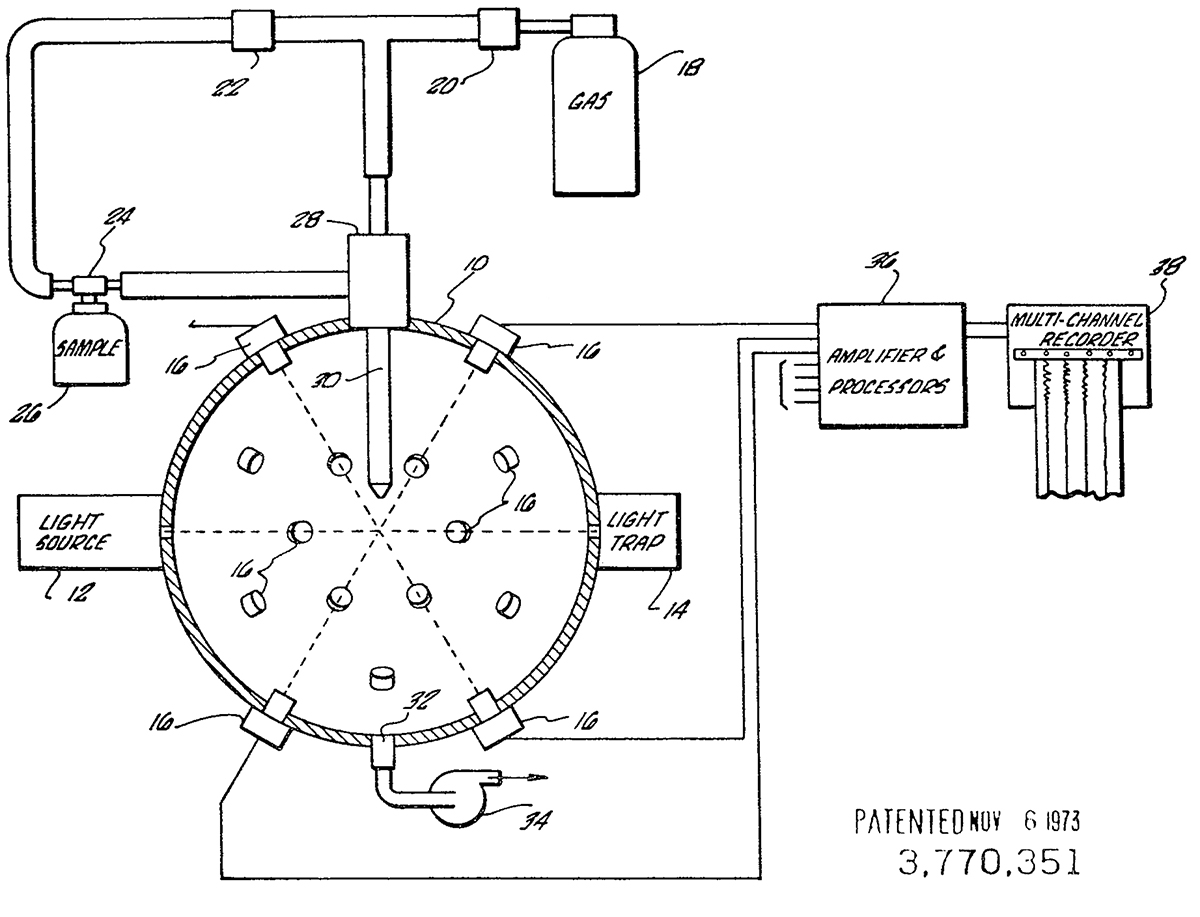

To say that its beginnings were modest understates the challenges that lay ahead. The Army was funding a $50,000 contract, but the money was not paid unless the work had been done. Progressive payment contracts work this way—but startups typically do not. Somehow, Dr. Wyatt (aka Dad and Phil) managed to resurrect a few instruments he had sitting in his garage, and began making the multi-angle light scattering measurements that would define the core of Wyatt Technology.

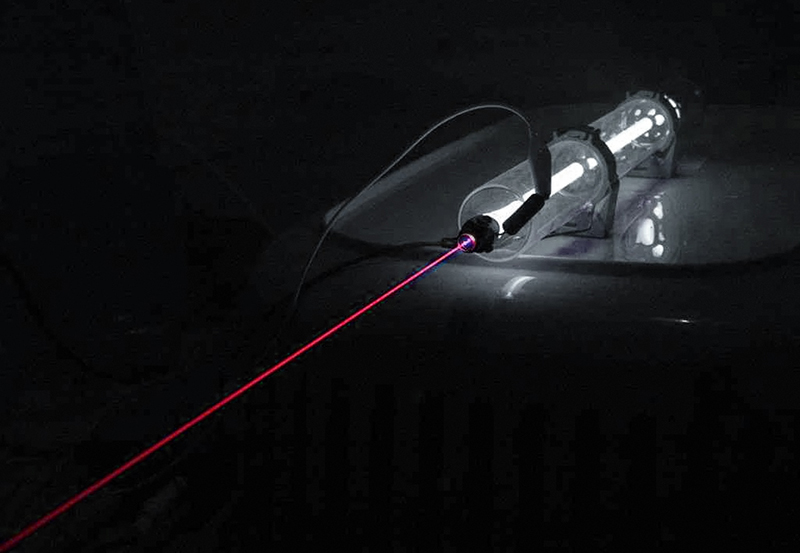

Dr. Wyatt’s work at Science Spectrum had established the company—and himself—as authorities of multi-angle light scattering instruments. To be sure, this was not necessarily saying a lot in 1981. Despite Science Spectrum’s groundbreaking use of early Intel microprocessor chips in its instruments, and the first commercial use of lasers in scientific instruments, light scattering was a little-known and seldom-used part of the analytical laboratories of the world. But, as the saying goes, you come into this world with a name and leave with a reputation, and by the early 1980’s Dr. Wyatt’s reputation was worldwide.

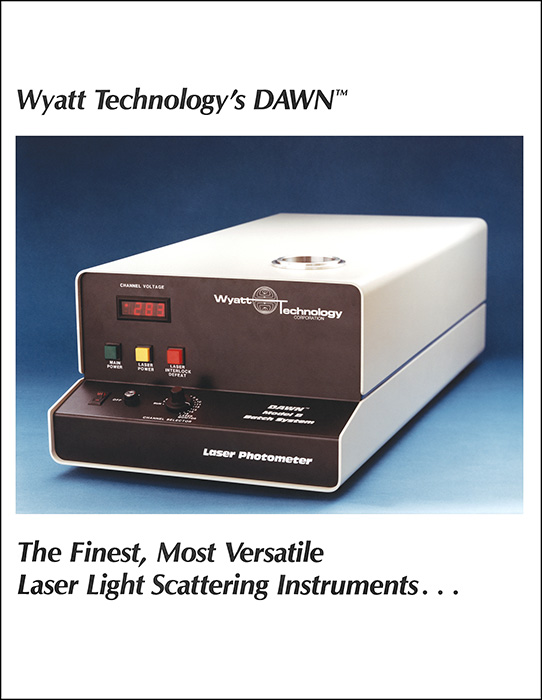

Dawn of the DAWN

Sometime in late 1982 or early 1983, Dr. Wyatt received a phone call from the Johnson Wax Company (the people who make floor waxes and polishes and a variety of other home-care consumer products). Johnson Wax wanted to know if Wyatt Technology (a company employing exactly one person) could build them a multi-angle laser light scattering instrument with flow through capabilities for chromatography applications. Bob Warner, the scientist at Johnson Wax, needed this detector for Hydrodynamic Chromatography (HDC). Phil Wyatt said he’d get back to them with a price and after a weekend spent consulting with an electrical engineering friend as well as a mechanical engineer who also ran a machine shop, Dr. Wyatt assembled a quotation, doubled the number, multiplied by Pi and presented it to Johnson Wax. The Racine, Wisconsin-based company accepted it almost immediately leaving Dr. Wyatt with the distinct impression that he could have and should have charged more!

By late 1983, three important things had happened to Wyatt Technology: Geof Wyatt, Phil’s oldest son, had been hired as full-time Employee #2, and the Johnson Wax instrument was ready to ship, and Phil had decided to name this first-born instrument DAWN. Now DAWN was not the name of an old girlfriend, or his wife, but in fact, an acronym for Dual Angle Weighted Nephelometry. And even though the DAWN for Johnson Wax had eight angles, Phil liked the name.

Geof wanted to know what Johnson Wax was going to do with its instrument, and Phil mentioned something about HDC, but encouraged Geof to contact Bob Warner and find out for himself.

Geof did, in fact, call Bob Warner, who explained that he was after a multi-angle light scattering detector for HDC, Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), and molecular weight determinations. The only detector available was a Low Angle Laser Light Scattering (LALLS) instrument sold by a company called Chromatix, but it was plagued by noise caused by the low angle of detection and the almost impossibility of getting solvents and samples clean enough to be able to distinguish one from the other.

Fruitful leads

While Geof understood almost nothing that Dr. Warner had told him, he wrote up a press release for a new product and sent it with a photograph of the instrument that had been shipped to Johnson Wax to scores of trade journals. What else was he supposed to do? Most of his time was spent helping his father make light scattering measurements of the bacterial response to toxicants, mutagens and metabolic poisons that the US Army contract had awarded the company.

This was late 1983 and early 1984, before the Internet had eradicated virtually all trade publications. In those days, trade journals published New Product Releases and had what were called reader service response cards (postage-paid, “Bingo” cards where the reader would circle the product number corresponding to the product(s) of interest). The magazine then printed out pre-addressed, gummed labels and sent them to each company whose product had been featured. The company, in turn, would send out product literature to the reader. This was the antithesis of instant gratification.

Phil and Geof were stunned when hundreds of leads poured into Wyatt Technology. There was just one small problem: Phil and Geof had nothing to send to the readers thirsting for more information on this DAWN Multi-angle Light scattering product! They had no brochure, they had no demonstration instrument, they had little idea what the instrument could do. So they employed some creative writing and finally produced a small, black-and-white brochure. With only the US Army $50,000 contract as income in those days, Wyatt Technology had virtually no financial resources available. Like so many things at the time, the brochures were produced on a shoestring budget, and envelope addressing, stuffing and even licking, were done by Phil and Geof.

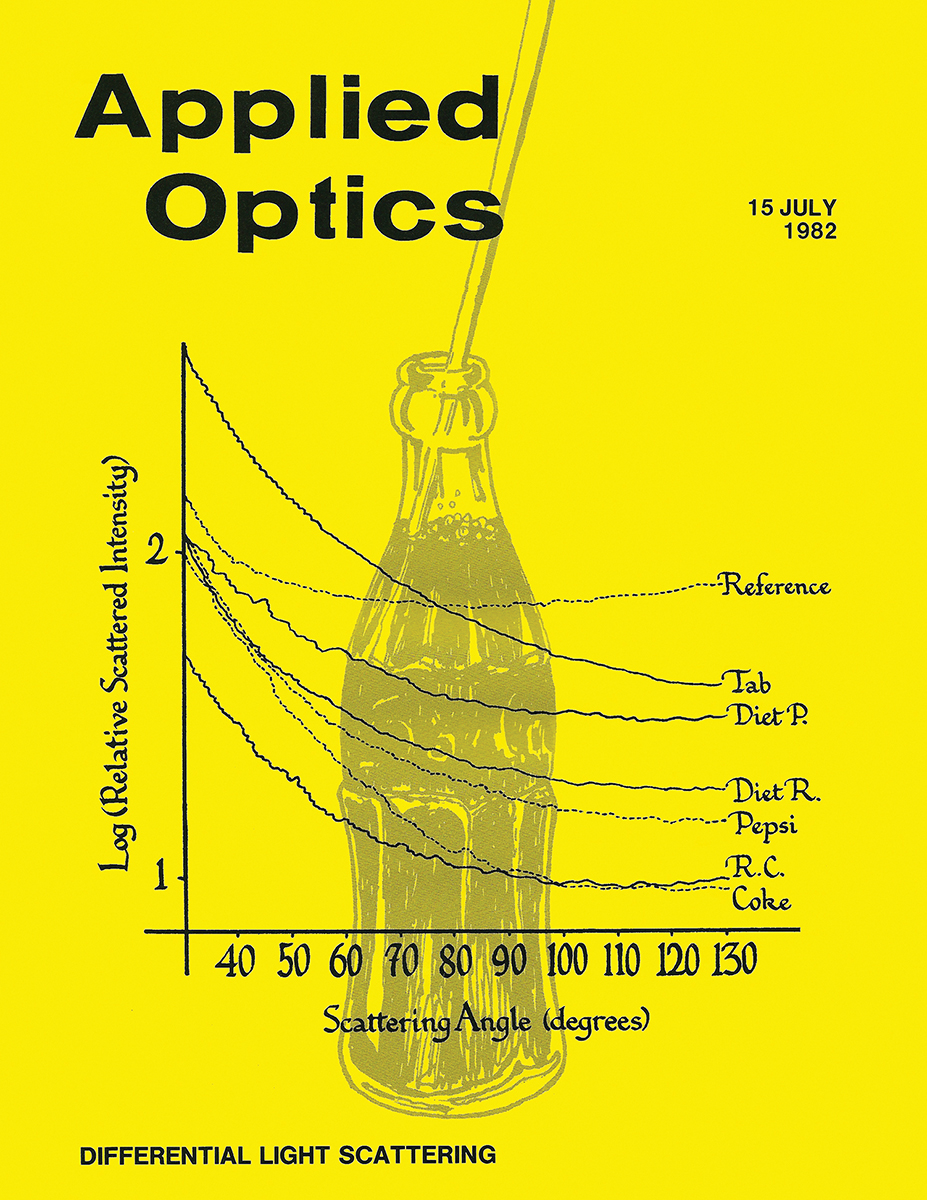

In early 1984, the Coca Cola Company become deeply interested in the multi-angle light scattering analyses of cola drink residues after discovering Phil Wyatt’s cover article for the 15 July 1982 issue of Applied Optics. Coca Cola was concerned that with our MALS technology that we might be able to deconstruct the magic formula for Coke that they call “7X.” The ensuing contracts with Coca Cola had little to do with their original formula and more to do with the kinds of things people put into their Coke bottles when they’re empty. It turned out that motor oil was one of the more popular liquids! The series of Coca Cola contracts that developed over the next couple of years bolstered the company’s precarious financial position, and even enabled us to hire a couple of people.

But a point of inflection for the company—although we didn’t know it at the time—came one afternoon in the Spring of 1984 when Mr. Joe Parli, from the AMOCO Production Company, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, called Wyatt Technology. Joe had read one of the New Product Releases and wanted to find out more about the DAWN. He explained to Geof that AMOCO had a Chromatix CMX-100 instrument, which was a Low Angle Laser Light (LALLS) scattering instrument. The extra “L” was added to the LALLS acronym (“low angle laser light scattering”) to symbolize “laser” reminding the user of the very narrow beam diameter facilitating small angle light scattering measurements.

The genesis for the Chromatix instruments had come from Dr. Wyatt’s previous company, Science Spectrum, in the 1970’s when Wilbur Kaye, of Beckman, had seen Science Spectrum’s laser-based instruments and concluded that microbiologists (to whom Science Spectrum was selling) would never be interested in something so sophisticated. Instead, he figured, analytical chemists were much bolder and willing to invest in advanced instrumentation. By 1974, Beckman Instruments had sold off its low angle laser light scattering (LALLS) device (introduced unsuccessfully in 1972) to Chromatix, which began further developments with measurements on GPC-separated polymer samples. Low angles are always noisier than higher angles, so making measurements at lower angles is always fraught with sample cleanliness issues. Still, purveyors of low angle instruments have come and gone over the intervening decades—each one proclaiming that you can change the laws of Physics!

Joe Parli was not at all happy about the noise that was overwhelming the signals he wanted to measure with his Chromatix. So he asked Geof, “You talk about multi-angles, what angles are they?” Geof said that just as with an air conditioner that has three settings: Low, Medium and High, so too, did the DAWN have low, medium and high angles. Joe asked for references and Geof pointed him in the direction of Bob Warner. In August 1984, Joe Parli placed an order for the second DAWN instrument. His application? Gel Permeation chromatography (GPC). In a short period of time Dr. Wyatt would refer to GPC as the acronym for Geof’s Pet Concept.

Rather than use the capillary-based flow system with seven angles of detection that Bob Warner’s instrument had, WTC delivered a new and improved system incorporating a cylindrical glass flow cell with 15 detectors spaced about it. This flow cell had almost mystical properties, or so claimed Dr. Wyatt, who discovered that the differences in refractive index between the solvent and the flow cell’s glass enabled measurements to be made at lower angles and higher angles than would have ordinarily been possible. Snell’s Law sometimes works in strange ways.

As DAWN instrument sales began to increase, ever-so-slowly, the government contracting business decreased. Wyatt Technology won notable Small Business Innovative Research grants from the Office of Naval Research (for a “laser troller”—effectively a multiangle light scattering instrument tethered to optical fibers more than a kilometer long), the NIH for looking at the effectiveness of AZT (an anti-AIDS drug), as well as follow-on funding from the Army that helped Wyatt Technology refine their instruments.

Hardware and software

While the first instruments came with RS-232 interfaces, and the first customers collected data and processed that data on minicomputers and the very first personal computers. But Wyatt Technology, with fewer than ten employees, had no software engineering and Phil and Geof frequently argued about the need for software. In 1985 the arguments reached a crescendo and Phil Wyatt banged his fist on his desk and declared “[Expletive deleted] if our customers are smart enough to buy our instruments they’re smart enough to write their own software!” Fortunately, the argument didn’t stop there, but in an ironic twist of fate, Wyatt’s first software programmer was none other than Philip Wyatt himself! And as a Physicist, he programmed in his preferred language: FORTRAN. Thus great oaks from little acorns grow.

Until about 1986 Wyatt Technology’s instruments were either DAWN F (F for Flow-through) or DAWN Model B (Batch mode light scattering measurements of samples in scintillation vials). There were no other products the company made. Joe Parli, from AMOCO, had found an interferometric refractometer made by a company called Tecator, in Sweden, that had been primarily used for Brix values, but that he was using for dn/dc determinations. This refractive index instrument had the ability to be built at a variety of wavelengths, thanks to its optical interference filters. Tecator called this instrument the Optilab, and it was not a simple instrument to build…as Wyatt Technology would soon find out.

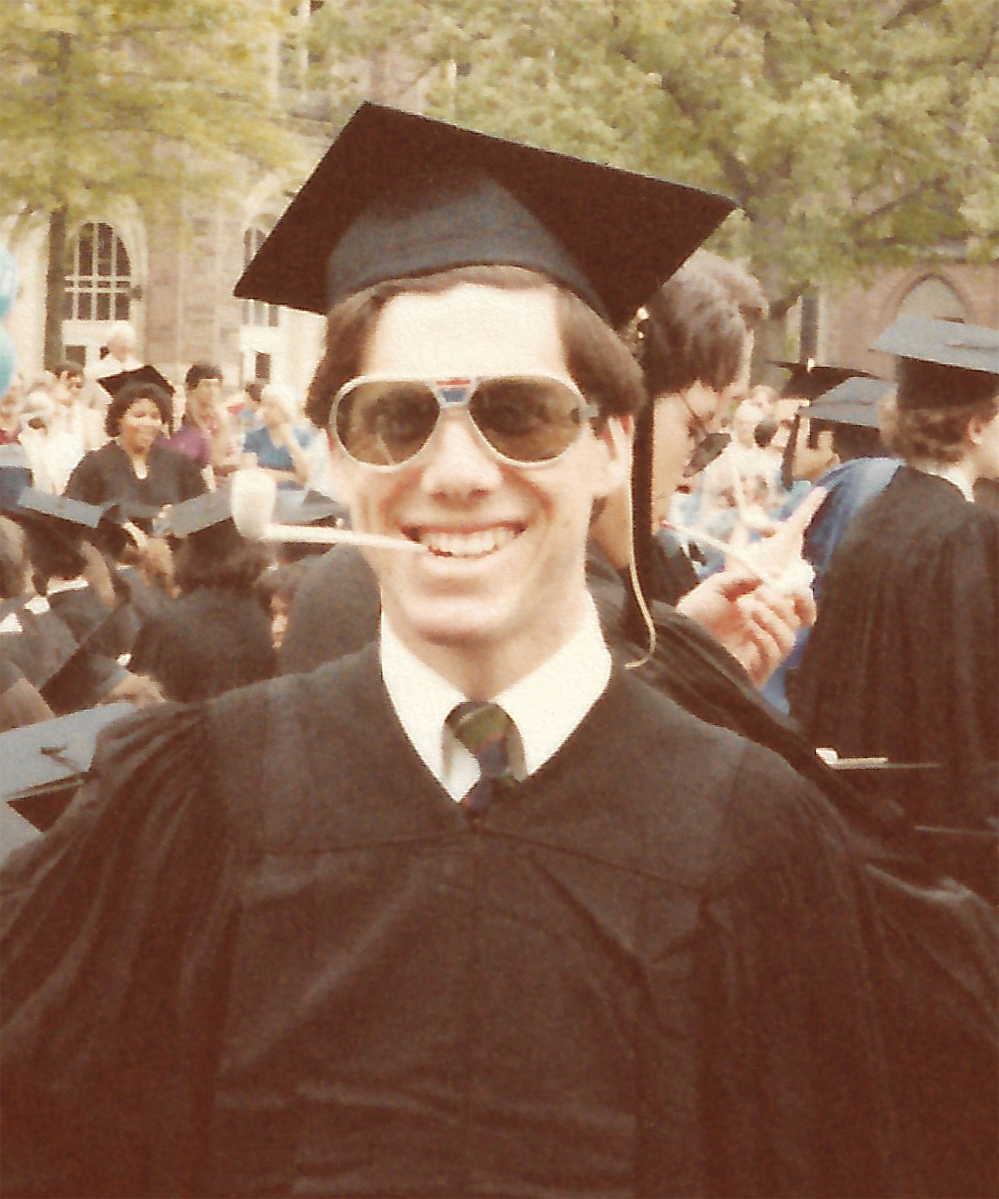

A roommate of Geof’s from college had encouraged him to apply to Harvard Business School, since Harvard had had more than its share of investment bankers and management consultants. Instead, it now sought people who came from real manufacturing companies. And by temporarily doing away with the GMAT exam, they hoped to appeal to people who weren’t superlative at test-taking. Geof took the bait, applied, was accepted and off to Boston he went in the Fall of 1987.

Having Geof out of the office gave Phil some breathing room. Within a year he had inked a deal with Tecator to purchase the Optilab product line for $100,000. This was Wyatt Technology’s very first corporate acquisition, and although no one knew it at the time, it set the pattern of acquisitions that were to follow. Among the many discoveries that Wyatt Technology made with the acquisition of the Optilab product line was the fact that there were no drawings for the parts. There was barely a Bill of Materials. And the few parts that had any description were in Swedish, which was not one of the languages that Dr. Wyatt spoke. Fortunately, as part of the purchase, Tecator loaned one of their technicians to Wyatt Technology to transfer the product. Ultimately, the parts were documented—in English—and a complete Bill of Materials was created. The company even began to sell Optilabs, painted “Wyatt blue” built for 488 nm wavelength, the same wavelength as Argon-ion lasers.

Those are a few of the early tales of Wyatt Technology's modest start. We want to thank our many customers and staff for helping us continue the process of bringing 40 years of technical innovation to market and making Wyatt Technology the company it is today - the recognized leader in instrumentation for determining the absolute molar mass, size, charge and interactions of macromolecules and nanoparticles in solution.

Read Part 2 below to learn about the technological evolution of light scattering!

Part 2: Gaining Momentum

Part 2

As the second employee of the company, Geof was given the lofty title of “Executive Vice President.” This looked especially impressive on the company’s business cards which, Phil insisted, should be engraved. These were not your ordinary Kinko’s business cards, the “500-for-$50” one would often see advertised. These cards were engraved on 100% cotton cardstock by one of the foremost printers in California, the Stuart F. Cooper Company.

For a company struggling to meet its meagre payroll, why did Dr. Wyatt insist on engraving the company’s letterhead and business cards? The short answer: quality. The longer answer was because of the impression (pardon the pun) that engraving gives to the recipient. With engraving, type and graphics are etched into metal plates and the recessed image is filled with ink. Once applied under the pressure of two tons per square inch, engraving leaves a raised image with startling clarity, color purity, and depth. If Wyatt Technology were going to build the finest, most versatile light scattering instruments on earth, they might as well have the finest business cards, too! And for the next thirty-plus years, we would.

One of Wyatt's early logos.

Dr. David Phillips, physicist with optics and electronics expertise, whose influence was felt for decades.

During the late 1980’s Dr. David Phillips, one of Dr. Wyatt’s colleagues from the Science Spectrum days, was hired to run Research & Development. David was already a Physicist with plenty of light scattering background from his work with Phil in the previous company. Besides his optics expertise, Dave was also a whiz at electronics and even software programming. David was an inveterate tinkerer, and his influence on the company’s products was felt for decades.

The software development efforts were a long time coming, and years before Geof ever went off to graduate school he and Phil argued about software with great regularity! Geof argued that the company desperately needed to develop software for the instruments, while Phil strongly disagreed. One afternoon, the argument reached new levels of volume. Geof advocated strongly that a programmer was desperately needed, and Phil finally had had enough. He slammed his fist on his desk and declared loud enough for the entire office to hear “If a customer is smart enough to buy our instruments, they’re smart enough to write their own [expletive deleted] software!”

The Cosmos works in mysterious ways and although neither of them could have predicted it, Phil Wyatt became the very first software engineer of Wyatt Technology. His frequent proclamation that “Physicists can do anything” was once again proven as he coded the first molecular weight determination software. The Zimm Plot measurements were primarily done in a batch mode with scintillation vials, although it was also possible to use the flow cell in a stopped-flow mode, too. This program was dubbed AURORA, to fit in the mold that the name DAWN had created.

The AURORA software was a command-line based program that ran on an IBM-PC, or compatible computer. In those days the computers had dual 5 1/4 “ floppy disk drives that contained a whopping 256K of memory. And, because he is a Physicist, Dr. Wyatt programmed in the language of Physicists: FORTRAN. The output of the program was sent to an Epson dot-matrix printer—there weren’t any laser printers in existence in those days. But this was the start of absolute macromolecular characterization.

Dr. Christoph Johann, one of the founders of PSS, Polymer Standards Services GmbH. PSS was the first company to represent Wyatt Technology in Germany.

From February 22-26, 1988 the Pittsburgh Conference was held in New Orleans, LA. The future of Wyatt Technology was about to change thanks to a young, newly-minted Ph.D. in polymer science from the University of Mainz, in Germany. Christoph Johann and a colleague had formed a company in 1985 called PSS, Polymer Standards Services GmbH, and they were starting a collaboration with Pressure Chemical Company. Larry Rosen, the president of Pressure Chemical, had invited Christoph to visit him and his company in Pittsburgh, as well as to join his booth at the Pittsburgh Conference exposition.

Christoph had heard about a new Company called Wyatt Technology which had introduced a light scattering detector called DAWN, which had the potential to perform better than the industry-standard Chromatix LALLS device. Christoph wanted to see if it could be used to characterize the molar mass of polymers his company was developing. Christoph stopped at the quirky booth of Wyatt Technology (which in those days didn’t have a booth and relied on wallpaper remainders for decoration). Phil Wyatt and Glenis Navarro (who had taken over Geof’s responsibilities while he was away at business school) answered Christoph’s questions and encouraged him to learn more.

Christoph was intrigued by the capabilities of the DAWN, so Phil invited him to visit the Wyatt facilities to test the instrument in the lab. Christoph accepted the offer, bought new airline tickets and went to Santa Barbara. There, he worked for a week with the DAWN, and obtained perfect results. Thanks to Larry Rosen, Christoph’s company was able to acquire a DAWN. PSS used it with great success, and the standards they made were marketed with absolute molar mass characterization giving them an edge against their competition. Christoph worked with the DAWN—and with Wyatt Technology—more and more and loved the interactions. He loved them so much that PSS began selling the DAWN in Germany as an additional product offering.

The 1988 Pittsburgh Conference was also the beginning of Wyatt Technology’s close relationship with Alfatech, Riccardo Braggio’s company based in Genoa, Italy, that would represent Wyatt to the present day!

In May 1989 Geof graduated from the Harvard Business School and returned to Santa Barbara with his roommate. Henry Stein was a “numbers guy”, who wanted to work in turnaround situations saving businesses from the messes they had put themselves in. But because no turnaround companies had hired Henry, Geof and Phil offered him the next best thing: the opportunity to help Wyatt Technology grow.

Henry became the CFO, and he helped recruit several new people to the company, including Carolyn Walton, who would be the company’s controller for more than thirty years, as well as Richard Thomas, a software engineer who’s been with WTC for thirty-two years, and counting! Henry’s experience in the United States Marine Corps also played a critical role in bringing discipline to the company not only in finance, but in manufacturing, product development, sales and marketing.

With a couple of people now working in software, and a total headcount of about a dozen employees, Wyatt Technology had made the transition from government contracting to commercial instrument sales. The company was selling the Optilab in addition to the DAWN Model B and DAWN Model F, and the software had been broadened to include a program called ASTRA, which became the company’s GPC chromatography platform.

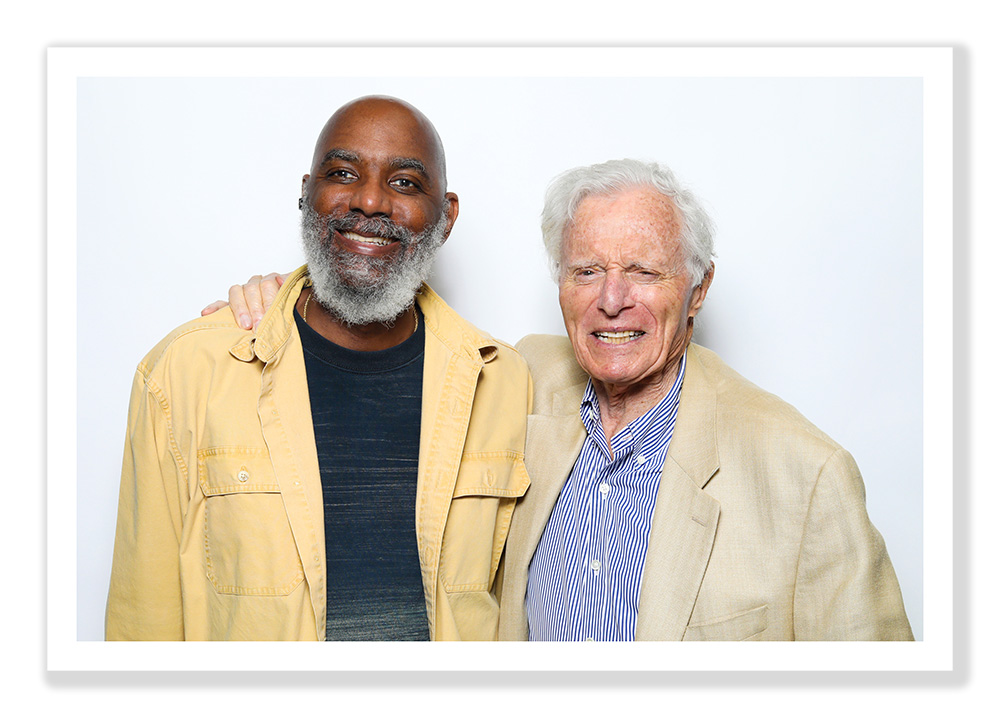

Richard Thomas, Principal Software Engineer, has been with Wyatt Technology for 32 years. Beside him is Dr. Philip Wyatt.

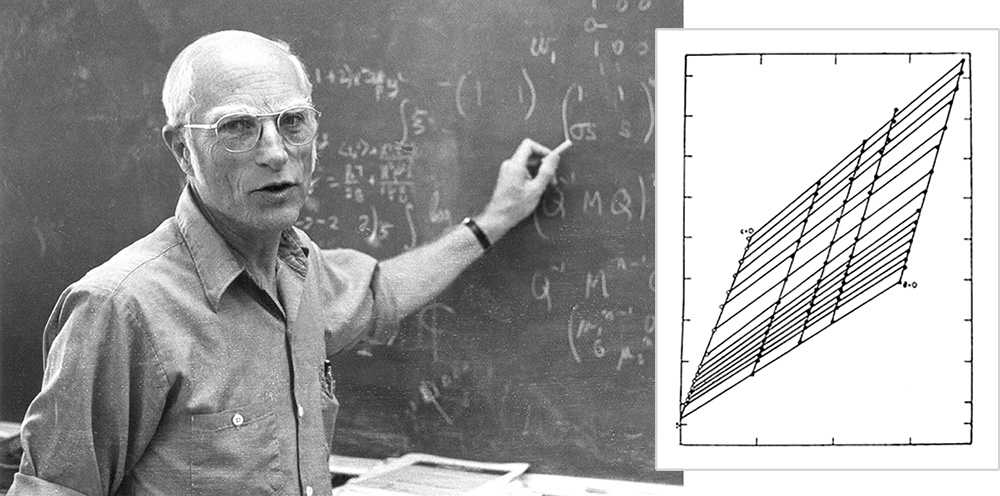

Bruno Zimm, inventor of the Zimm Plot and consultant to Wyatt Technology in its early days.

Wyatt had a secret weapon in helping to guide the AURORA and ASTRA programs and their determination of molecular weights and sizes. Professor Bruno Zimm had been introduced to the company courtesy of Professor Harold Morowitz (the Master of Geof’s college at Yale). Geof had asked Harold if he knew Bruno Zimm, and Harold had replied “Of course! I remember a meeting we both attended and when we weren’t discussing science we discussed the optimal shape for the sails for our sailboats!” Harold added that Bruno was “ominously intelligent”, and it’s fortunate for us all that he used his powers for good and not evil!

As the eponymous inventor of the Zimm Plot, Bruno was the perfect person to join Wyatt Technology’s SAB (Scientific Advisory Board). He became a celebrity among Wyatt customers in the years to come, starting with the International Light Scattering Colloquium, better known as the Wyatt Technology Users’ Forum.

Phil Wyatt always hoped that one day the company would have user-meetings like a company he had been acquainted with in his Science Spectrum days, called Technicon. As he explained it, Technicon created trade shows for themselves and their customers. This was the model that prompted Dr. Wyatt to conceive of the International Light Scattering Colloquium, or ILSC for short!

In 1989 Wyatt Technology held its First Annual Users’ Forum at the Montecito Inn. There weren’t many people there, but there were enough important customers to justify bringing Bruno up to Santa Barbara via Amtrak. Among these customers was a woman who would become one of Wyatt Technology’s heroes, Dr. Patricia Cotts, from IBM’s Almaden Research Labs at 650 Harry Road, in San Jose, California. Pat joined Bob Warner and Joe Parli as part of the metaphorical Pantheon of Wyatt’s most influential customers.

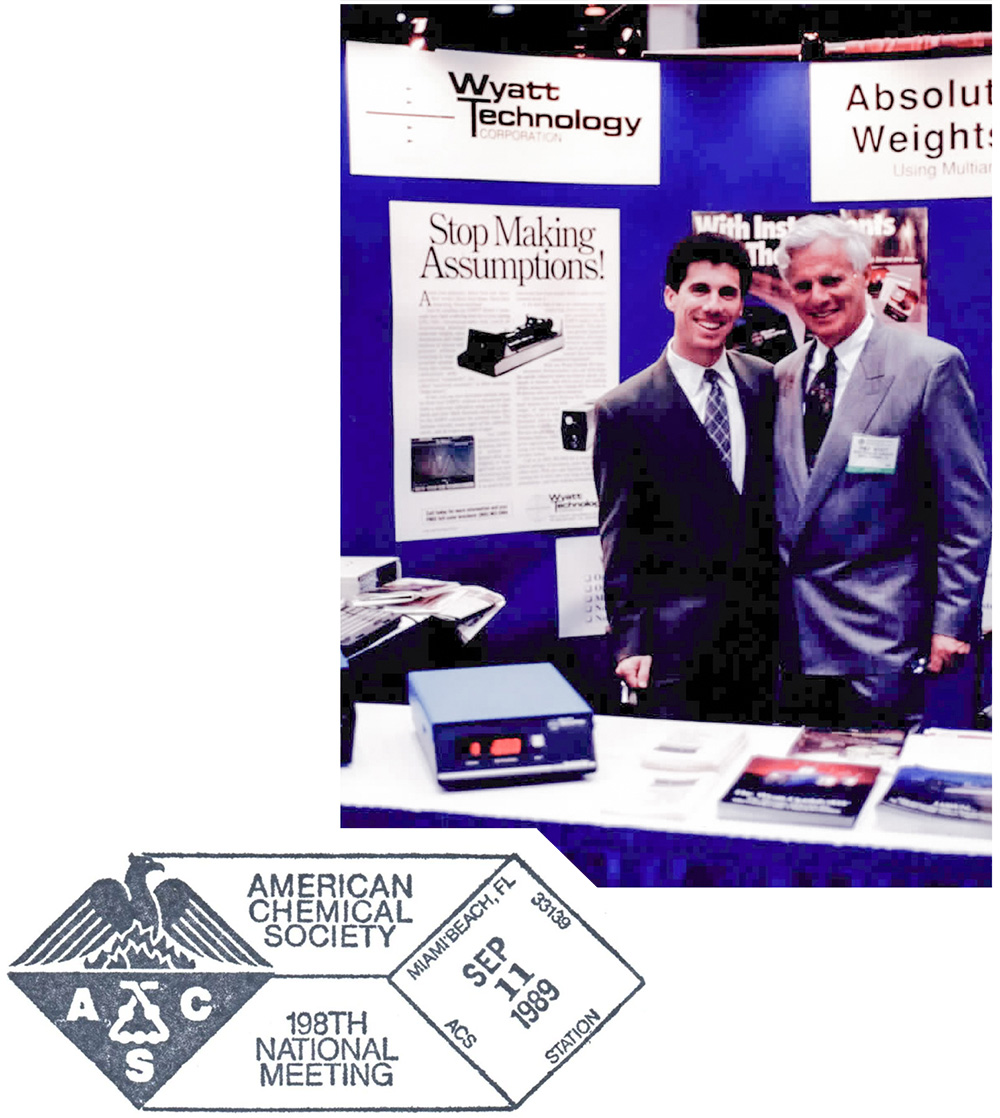

September 10-15, 1989 marked the American Chemical Society’s 198th national meeting in Miami Beach, FL and the Fontainbleau Hotel as the venue for the exposition. Geof attended the meeting and had no idea how an instrument on display at another booth would change the course of the company’s future and its reputation as a pugnacious competitor. If he didn’t let out an audible gasp when he stopped at Polymer Laboratories’ Booth #703, then it was so internally loud that he was surprised no one else heard him. There, on display, was a static and dynamic light scattering instrument that Geof had seen before. It was a Japanese-made instrument, renamed and rebadged as the PL-LSP. This Light Scattering Photometer (LSP) was computer controlled, powered by a 5mW He-Ne laser, had a high speed correlator inside to make dynamic light scattering measurements, and it had a photomultiplier for static light scattering detection.

While it didn’t have flow-through capabilities, it had just about every other “bell and whistle” customers could ask for. And, similar to Dr. Wyatt’s instruments from Science Spectrum, the photomultiplier scanned the sample using a computer-controlled stepper motor. Geof obtained a price list and found that it was being sold by Polymer Laboratories for $48,750. A differential refractometer was available for an additional $14,500. When Geof returned to Santa Barbara he learned more about the device: it was manufactured in Japan by Photal, a multi-million dollar division of Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, a multi-billion dollar conglomerate. Wyatt Technology’s representative in Japan was able to obtain Photal’s Japanese price list that showed that this product, called the DLS-700 in Japan, cost 12,800,000 Yen, or approximately $130,000. So how was it possible that this same product could travel 6,000-plus miles and be sold to end-users for only $48,000? This seemed to defy the laws of physics, or at least economics!

Geof went into his father’s office and told him the story. With an airy wave of his hand, Phil said “Call the U.S. Department of Commerce and have them impose anti-dumping duties!” As Wyatt Technology would soon discover, nothing could have been more difficult.

Part 3: David versus Godzilla

Part 3

As mentioned in the last chapter, the ACS Show in Miami Beach took place in 1989—a year in which many readers of this history may not even have been born! Some of the ways in which business was conducted then were similar to those of today, but others were very different. While most business communication today seems to avoid the telephone almost entirely, in 1989 it was an indispensable tool.

There was no Internet (and no Google, Yahoo or Baidu) to find out the telephone number for the U.S. Department of Commerce. In 1989 you had to dial the area code of Washington, DC, and then “555-1212”. So Geof dialed 202-555-1212. A telephone operator answered and promptly gave Geof the number. Perhaps even more surprising, when Geof dialed the number, a human being at the Department of Commerce picked up the phone! Thus, was launched Wyatt Technology’s odyssey into economic dumping.

“Hello, my name is Geofrey Wyatt and I’m the Executive Vice President of Wyatt Technology, located in Santa Barbara, California,” Geof began, “We have a fax that shows that the price a Japanese instrument is selling for in the US is less than it sells for in Japan and I’m calling to ask you to please impose dumping duties on them!” When the laughter at the other end of the conversation died down, Geof was transferred to someone who explained to him what needed to be done.

As we quickly learned, Wyatt Technology had to start the process not with the US Department of Commerce, but at the International Trade Commission (ITC). There, not only did Wyatt Technology have to prove that the Japanese equipment was being sold at Less Than Fair Value (LTFV), but we also had to prove that the Japanese instrument was a “Like Product”. Moreover, we had to show that there was a domestic “industry” of laser light scattering products, and that because of LTFV imports we were either being materially injured or being threatened with material injury. To a lawyer these may seem perfectly straightforward, but neither Geof nor Phil nor anyone else employed at Wyatt Technology was a lawyer, let alone one who specialized in international law. WTC had no legal counsel, and the costs to retain proper counsel on an anti-dumping suit easily began at $500,000—in 1989 dollars (about $1.2 million today).

Because WTC couldn’t afford legal representation, we could represent ourselves…with a little help from the International Trade Commission’s (ITC) Trade Remedy Assistance Office. They would help us format our documents properly, make sure they were served to the right parties, and that we played by the rules. When we asked if anyone else had ever represented themselves in an anti-dumping case successfully, we were told “No.” No one had ever won without a law firm representing them. Cue the foreboding music!

Geof was quickly schooled in how anti-dumping cases proceed and how the bifurcated process works: first the case is handled by the International Trade Commission (ITC). The ITC determines whether there is damage to or threat of damage to the US “industry”. If this bar is met, then the ITC refers the case back to the U.S. Department of Commerce, who investigates the entity supplying the goods in questions and then determines the amount of duty that should be assessed.

From WTC’s perspective, the anti-dumping case we were bringing before the International Trade Commission couldn't have been more intimidating: in 1989 we were a company of maybe twenty people and less than two million dollars in annual sales. They numbered in the hundreds, and their annual revenues were more than a hundred million dollars.

Most frightening was the fact that the “they” referred to weren't our Japanese adversaries; “they” were Arnold & Porter, the attorneys hired by the Japanese to represent them! To us, “David versus Goliath” had morphed into David versus Godzilla. If Arnold and Porter weren’t large enough to satisfy most believers in Greek tragedy, then Otsuka Electronics—a multi-million dollar division of multi-billion dollar Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, was there to convince them. And everyone knows what happens at the end of a Greek tragedy: the hero dies!

When Dr. Wyatt learned that Otsuka had hired legal counsel (we didn’t know whether they would or would not, up until just a few days prior to the first public hearing in Washington) he asked Geof who was representing them. Geof said “I’ve never heard of them, but the letterhead says Arnold & Porter.” Dr. Wyatt uttered a variation of “Oh, nuts!”—replacing the nuts with an expletive not appropriate for this family history.

“Arnold & Porter is one of the largest and most prestigious law firms in the country, Geof! It used to be called Arnold, Fortas & Porter, until Abe Fortas was appointed by Lyndon Johnson to the Supreme Court!” Then it was Geof’s turn to utter a profanity or two.

Every legal step of WTC’s anti-dumping case just seemed to accentuate our diminutive size and lack of resources; our opponents never lacked for financial or personnel resources in the form of partners, associates, legal clerks, expert witnesses, as well as infinitely deep case law expertise.

Had we known what the odds against us were, or how much time and effort and emotion we would burn putting our case together and arguing it before the International Trade Commission as well as the U.S. Department of Commerce, we never would have filed our initial petition against Otsuka. As it turned out, our ignorance became our biggest advantage. We thought that every brief we wrote was surely the last, so all our efforts went into making each one as strong as possible.

In hindsight, this situation reminded Geof of a passage from Mark Twain who said “But don’t you know, there are some things that can beat smartness and foresight? Awkwardness and stupidity can. The best swordsman in the world doesn’t need to fear the second-best swordsman in the world; no, the person for him to be afraid of is some ignorant antagonist who has never had a sword in his hand before; he doesn’t do the thing he ought to do, and so the expert isn’t prepared for him; he does the thing he ought not to do: and often it catches the expert out…”

Over the course of a year we would write thousands of pages of legal “briefs” (a misnomer and legal joke we laypeople can now appreciate), go to Washington for two separate hearings, craft legal arguments never heard before the ITC previously, and, ultimately, beat Arnold & Porter as well as the firm that would later represent Otsuka, the prosperous Los Angeles law firm: Irell & Manella.

The trade laws of the United States can be very strange. Any other nation would give every benefit of the doubt to its own industry. Not so in the U.S. As we learned in experience after bitter experience, the burden of proof always clung to our shoulders. But this didn't seem fair. Wyatt Technology was a scrappy, high-technology company that was creating jobs, paying taxes, and making products that would help in developing life-saving therapeutics.

Perhaps most unfair, at least in our non-legal minds, was the legal system known as APO—Administrative Protective Order. Under APO, a client's attorneys have the right to see all proprietary information from their adversaries. Attorneys are sworn not to divulge such information to their client, but it is difficult for me to understand how transgressions never exist.

Indeed, since Wyatt Technology had brought its case before the ITC pro se (on our own behalf), and since Otsuka Electronics had hired Arnold & Porter, A&P (and later Irell & Manella) had the right to see all our sales figures, cost tables, manufacturing and marketing strategies while we were not allowed access to any of Otsuka's proprietary information.

The last legal outrage occurred just prior to our final hearing when Irell & Manella—sensing that even with all their manifold advantages that they should increase their odds of winning—requested that the final hearing be held in camera so that proprietary information could be discussed. Notwithstanding the fact that the final hearing is meant to be a public event, Irell knew that since we were representing ourselves, we could not attend the in camera session since only people protected under APO could attend! It was legal hardball at its best, but our arguments prevailed that if they had something confidential to report, that they should do so in their briefs and not in confidential hearings in which even we wouldn’t be allowed.

The best analogy for our situation regarding confidential information was of a poker game in which one player (Wyatt Technology) must have all of his cards face up on the table, while his opponent can keep all of his cards face down. APO survives, and encourages—if not compels—companies to hire professional legal counsel. We, however, could not afford legal counsel, so we relied upon our card-playing skills to stay in the game. Bluffing, of course, was out of the question since our cards were visible at all times.

Trade disputes are by their very nature expensive, prolonged legal battles. An anti-dumping action is not relegated solely to the International Trade Commission; in fact, the system is bifurcated: as indicated before, injury—or threat of injury—is determined by the ITC, while actual dumping duties are calculated by the Department of Commerce. The ITC itself is comprised of six Commissioners, each of whom is appointed by the President of the United States, with approval of the Senate. But unlike packing the Supreme Court, the ITC thwarts this tendency because it must have at least 3 members of both political parties on the bench. It is quite common; therefore, to have a Republican president forced to appoint a Democratic Commissioner. Just imagine if our Supreme Court nomination procedure had the same requirements!

A petition is filed first with the ITC whose Commissioners decide whether there is reasonableness to the case. If there is, the case is handed to the Department of Commerce who calculates by what margin “dumping” may be occurring. Once this has been completed, the DoC hands the case back to the ITC for a final determination of whether injury exists to the domestic industry. If the petitioner loses just one round before the final hearing, the entire case is lost.

Apart from proving that the Japanese instrument was being sold at LTFV, we also had to prove that we represented a domestic industry and that we were being injured or threatened with material injury. Our laser light scattering photometers are expensive, specialized analytical instruments that are used by chemists and biochemists in the chemical, petrochemical, pharmaceutical, biotechnological, as well as academic and government research settings. To us, who were intimately familiar with our products, there was no essential difference between our product and the Japanese one. To a legal mind, however, the differences were considerable! In fact, many of the legal skirmishes we fought were over this very issue of “Like Products.” The respondents put great emphasis on this matter, since it would have ruined our case had they proved our products to be different.

The laser light scattering instrument industry—if such an orderly definition can even be applied—was, at that time, fragmented among four or five different producers, all of whom were small companies (20 or fewer people), run by physicists—none of whom will agree on anything! This fact alone made it difficult for us to bring our case before the ITC since we had to prove that we were representing the industry! While we—and other U.S. manufacturers—talked about “free enterprise”, we all disagreed about what constituted a “level playing field.” Ultimately, we were able to prove that we were representing the light scattering instrument industry, but not without cajoling our competitors in what seemed more like political campaigning than trade warring.

Complicating the case—for us as well as for the ITC—was the fact that we didn’t sell hundreds of instruments a year. Consequently, each sale is vitally important to us. Furthermore, although an instrument can have a useful lifetime of 5-10 years, some companies may purchase more than one. Word-of-mouth advertising is as important as any other factor, so if you lose one sale, you may lose more than that downstream. Over time, the consequences can mean either that you lose all of your business, or gain enormous market share. Our strategy was to prove the enormous threat of material injury because of the “cascade” effect current lost sales would have on future sales.

The nature of many high-technology businesses is that they have very high fixed costs; regardless of the amount of business that they transact, their costs to keep their doors open are very high. Once the fixed costs of the business have been met, however, any additional, or incremental revenue falls almost directly to the bottom line. In our arguments supporting injury, we claimed that just one lost sale harmed us—and we comprised a majority of the U.S. laser light scattering industry. We even showed that we had lost a sale, but the ITC were so used to hearing cases about commodity products (TV’s, radios, CPU’s, and automobiles), that one lost sale was wholly unimpressive.

Some arguments made by the defense claimed that one lost sale was insignificant, even for us. But we countered with an assertion that gave everyone some pause: we were not going to go down as the U.S. car industry, semiconductor, television or textile industries had. We recognized that we were before the ITC at an early date, but this was intentional. We didn't want to be before them on our knees. It amazes us that so many of our domestic industries that may have had legitimate dumping claims were either too parochial or arrogant about their businesses to recognize nascent threats to their survival.

At one point during an off-the-record argument with an attorney at Arnold & Porter, Geof said that he thought that WTC should be given a finder's fee for all of the business that Arnold & Porter had been able to bill. The response we got was simple; the attorney told us that the best things about his Japanese clients were that “they never question the bill, and they always pay on time!”

The “revolving door” of government employees and paid consultants even affected our case. After losing the first hearing before the ITC, Otsuka fired Arnold & Porter (oh, to have been a fly on the wall of the conference room in some Japanese skyscraper when Otsuka saw what had happened!) and hired Irell & Manella who trotted out their legal team that included the former Chairman of the ITC, the former chief of staff of the then current chairman of the ITC, as well as an econometric consulting firm founded by former employees of the ITC! Wyatt Technology had no such connections. In fact, when we tried to bring some political weight to bear, we received lukewarm letters written on our behalf from then Senators Alan Cranston and Pete Wilson. And instead of fire and brimstone invectives urging the ITC to find for the petitioners (WTC), the letters cordially requested that the ITC be as evenhanded as it could be.

When it was all over and the commissioners voted their decision, Wyatt Technology won—by a tie vote! The one and only advantage given to the domestic industry rests with the commissioner's vote where, as they say in baseball, “the tie goes to the runner.” In this case, because we were the home (domestic) team, we won.

Seriously outgunned by infinite legal talent, WTC had argued the facts—which we knew better than the lawyers ever would. They, on the other hand, kept citing case law, which in this case was never compelling because their citations never came close to describing the industry or conditions which were present in our case.

WTC’s tie-vote triumph wasn't resounding, but it was enough to trigger the Department of Commerce into notifying the U.S. Customs Agency to begin imposing 129% duties on light scattering instruments and parts thereof from Japan! And when it was all over Wyatt Technology went back to doing what it should have been doing all along: developing, building, selling and supporting the world's finest and most versatile laser light scattering instruments.

We found a terrific partner to sell our products in Japan, and from about 1991 onwards, Shoko Scientific (a division of Showa Denko) successfully represented us. Shoko took the fight to Japan and won market share away from Otsuka. An accomplishment that endures to this day.

But more adventures lay ahead, as you’ll see in the next installment of this history!

Part 4: Getting the Word Out

Part 4

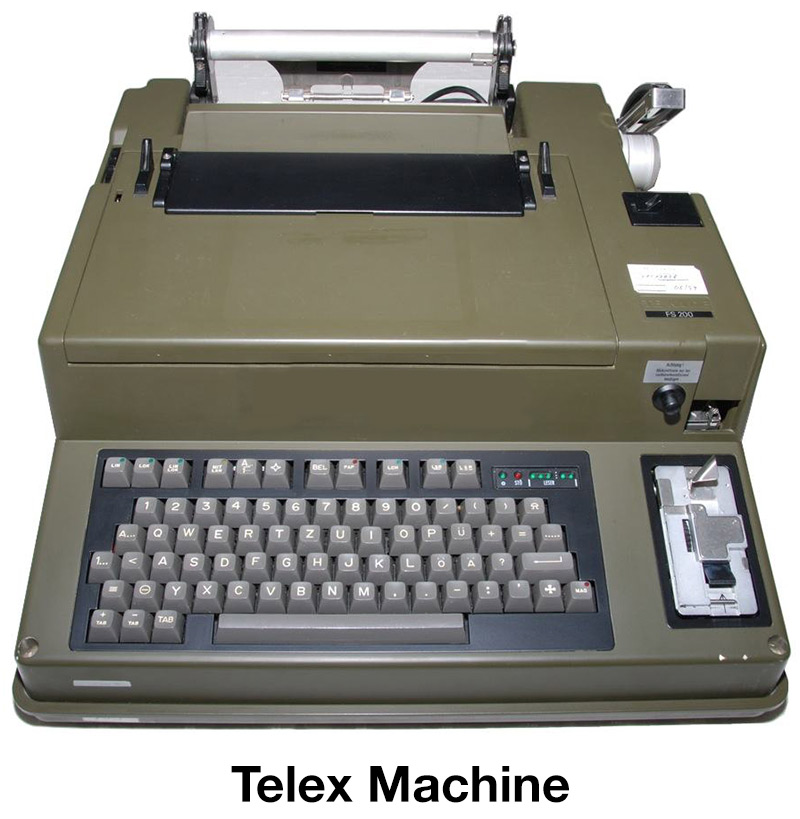

When Wyatt Technology began operating, international corporate communications frequently used Telex machines (combinations of printers and telephones). They transmitted information at the now-glacial pace of 50 baud, which equaled about 60-70 words per minute. If you were sending a message to the UK, or India or Japan, for example, the cost of the transmission was directly proportional to the length of time of the connection. And reaching out to touch someone by Telex, in those days, was not an inexpensive proposition.

In 1989, the cost for one minute phone call to Europe or Asia could be anywhere from $4.00 to $7.00, depending on the time of day. Because WTC lived a “hand-to-mouth” existence for its first few years, we would use a friend’s company’s Telex machine, but soon found that a nascent service called MCI Mail—which could run on our early IBM-compatible PC’s—only cost 50 cents to send and receive messages. Wyatt Technology’s Telex address was 650 288 6806 and really was the precursor to email. A Telex machine would have been more fun to have—since they chattered as loud as a child banging on the keys of a manual typewriter—but they were expensive. Besides, with the word “Technology” in our name, we had to have something and MCI Mail was better than nothing.

Soon enough, by the late 1980’s, the fax machine supplanted MCI Mail, but for every page break sent by fax, the fax machine had to send information to the receiving machine to cut the paper. This took expensive, long-distance time. Being a physicist and understanding that even though the speed of light was fast, Dr. Wyatt taped the pages of Wyatt Technology’s faxes together. This saved considerable transmission time, although it did result in extraordinarily long scrolls of paper that the sender and the receiver had to deal with! In those days there were two types of paper you never wanted to run out of: fax paper for the fax machine, and toilet paper for the bathrooms!

In late 1990 Tim Berners-Lee had built all the tools necessary for the Internet to work: HTTP and HTML. Within a couple of years, it became apparent that the Web was here to stay and was going to be a powerful business tool. Email, as well, went hand-in-hand with the Web. When Dr. Wyatt had the chance, he pounced on the domain name “wyatt.com” for the company (To be exact, the date was February 24, 1994).

Since the beginning of WTC’s formation, and for decades before, the world had been marching towards solid-state electronics. While Science Spectrum had used photomultiplier tubes, Wyatt Technology had been able to use transimpedance silicon photodiodes. And by the early 1990’s the time had come to leave gas lasers (like Helium-Neon) and replace them with a new class of lasers made of solid state materials. The miniDAWN, a three-angle instrument, launched in 1992, incorporated a Gallium Arsenide (GaAs) laser, making it our very first solid state instrument. It would be seven more years before the DAWN EOS (Enhanced Optical System) would be introduced to replace our He-Ne laser in our flagship product with a solid state laser. The launch of the miniDAWN was itself a controversial move. All of a sudden, WTC would be selling an instrument at roughly half the price of the DAWN, but that would require similar levels of service and support.

The marketing concept of “cannibalization” proposed that the miniDAWN would eat into sales of the higher-priced DAWN instruments, and the total number of DAWN units sold would decrease. This wasn’t just some theoretical debate going on in the company, it seemed like a struggle without a solution. A two-angle light scattering instrument had appeared on the market, made by a company called Precision Detectors. It consisted of a “low” angle detector at 15° and another at 90°. Its presence was already starting to eat away to sales of the DAWN, so it seemed like there was no choice but to launch the miniDAWN come what may.

Further investigation revealed that Precision Detectors was infringing some of the DAWNs patents, and, in pugilistic form, Wyatt Technology sued Precision Detectors in federal court. After months of legal wrangling, and an impending court date, WTC and Precision Detectors settled out of court so that for every instrument PD sold, they would pay a royalty to WTC. This settlement was signed in late 1994 and lasted for a period of about 5 years. Interestingly, the launch of the miniDAWN did not diminish DAWN sales at all. Much to the surprise of everyone at WTC, a new market was created for those people who couldn’t afford a DAWN—as well as those who didn’t need the then 16 angles of detection. The family of light scattering instruments was indeed expanding.

One of the seeds of Wyatt Technology’s future growth was planted in December 1989 when Barbara O’Connor purchased a DAWN for Genentech, the world’s first successful biotechnology company, located in South San Francisco. Alan Herman, a friend and a colleague of Barbara’s at Genentech, had moved to Thousand Oaks, California. There, a nascent biotechnology company called Amgen was beginning to flex its muscles with the approval of its recombinant erythropoietin product, Epogen, in June 1989.

Barbara had been successful in using her DAWN (and Optilab!) coupled to a Gel Filtration Chromatograph, and Alan had gotten positive feedback on her experiences working with Wyatt. In October 1990, Alan purchased a DAWN for his lab—the first at Amgen. The sale to Amgen turned out to be more serendipitous than anyone could have imagined because the distance between Santa Barbara and Thousand Oaks was only fifty or sixty miles. When something went wrong with Alan’s instrument, he put it in his car and drove it up to Santa Barbara. While a technician repaired it, we took Alan to lunch. When we said that we would be delighted to come and get the instrument from his lab to save him the trip, he reminded us that he “loved coming to Santa Barbara!”

When a software glitch arose, one of our programmers could easily drive to Amgen to see what was going on in their laboratory and observe their work flow. Nowhere else on earth could our service and support be any better—especially because we only employed a handful of people at the time! Due to our proximity to Amgen, we were able to learn far more about the challenges of making measurements of proteins than we had been able to when Genentech had had problems. Genentech was a six hour drive from Santa Barbara—not nearly as trivial a trip as the hour-long commute to Thousand Oaks.

Merck ordered their first instrument in West Point, PA in June 1991. It was a world away from Santa Barbara, but their scientists, led by Bohumil Bednar and John Hennessey, applied the DAWN and Optilab system to polysaccharides, and their publications on the size analysis of capsular polysaccharide preparations put Wyatt on the map in the biopharma world.

The 1990’s saw WTC move away from its government contracts, which had given the first breaths to the company and enabled the development of the first instruments, to purely commercial instrument sales. As Wyatt Technology Deutschland (as it was called prior to 1998) began to grow its sales, and as word of mouth began to spread the awareness of MALS, Phil and Geof searched for someone to take their instrument sales to the next level. Fortunately, salvation was on the horizon.

Cliff Wyatt had graduated UC Berkeley with a degree in Genetics, and had even done a year abroad at Cambridge University. He had been immersed in sales since joining Becton Dickinson selling blood analyzers to doctor’s offices in the Pacific Northwest, and then began selling really large diagnostic instrumentation for Bayer in the same region. He was living in Seattle, enjoying the eleven and a half months of winter and half month of summer, when he was approached by his father and brother.

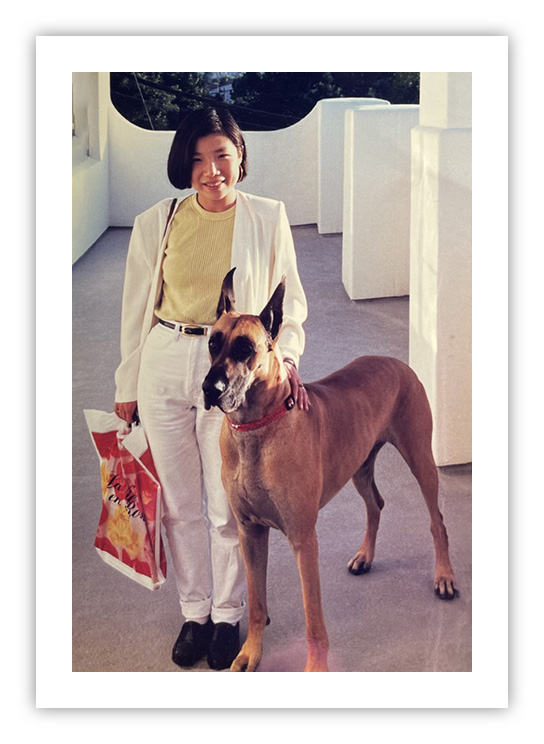

Phil and Geof had concocted a plan whereby they would offer Cliff half as much pay, but work him twice as hard, and let him take Phil’s Great Dane, Einstein, downtown Santa Barbara to meet young ladies. Since Cliff was single at the time, and at the prospect of strutting the magnificent Einstein downtown, he confused the numerator and denominator of the proposition and accepted on the spot! Wyatt Technology at last had some firepower in the sales department.

On September 1, 1996 Clifford Wyatt officially joined Wyatt Technology. If it hadn’t been a family business before, it certainly was now! The triumvirate of Phil, Geof and Cliff began attending loads of trade shows together. And thus began at least a decade of room-sharing among the three of them! Hotel rooms then were every bit as expensive as they are now, and to save the company money, the three Wyatts bunked in the same room. Of course, because he was the youngest, Cliff often ended up with the rollaway!

Another critical employee was added to the team just before Cliff, in June 1996: Dr. Michelle Chen. Michelle’s Yale Ph.D. in the lab of the world-renowned scientist, Csaba Horvath, who had built the first HPLC, was another critical piece of the puzzle since so much business was coming from the chromatography world. In 1997, Dr. Steve Trainoff came into the fold after moonlighting as Wyatt Technology’s NeXT computer savant for several years! Steve’s background as a Ph.D. physicist, from the lab of Professor David Cannell at UCSB, instantly appealed to Phil. Steve would help ignite even more innovation WTC needed to continue its growth trajectory.