Celebrating 40 years of technological innovation

Part 1: The early years

Narrative by Geofrey Wyatt, CEO

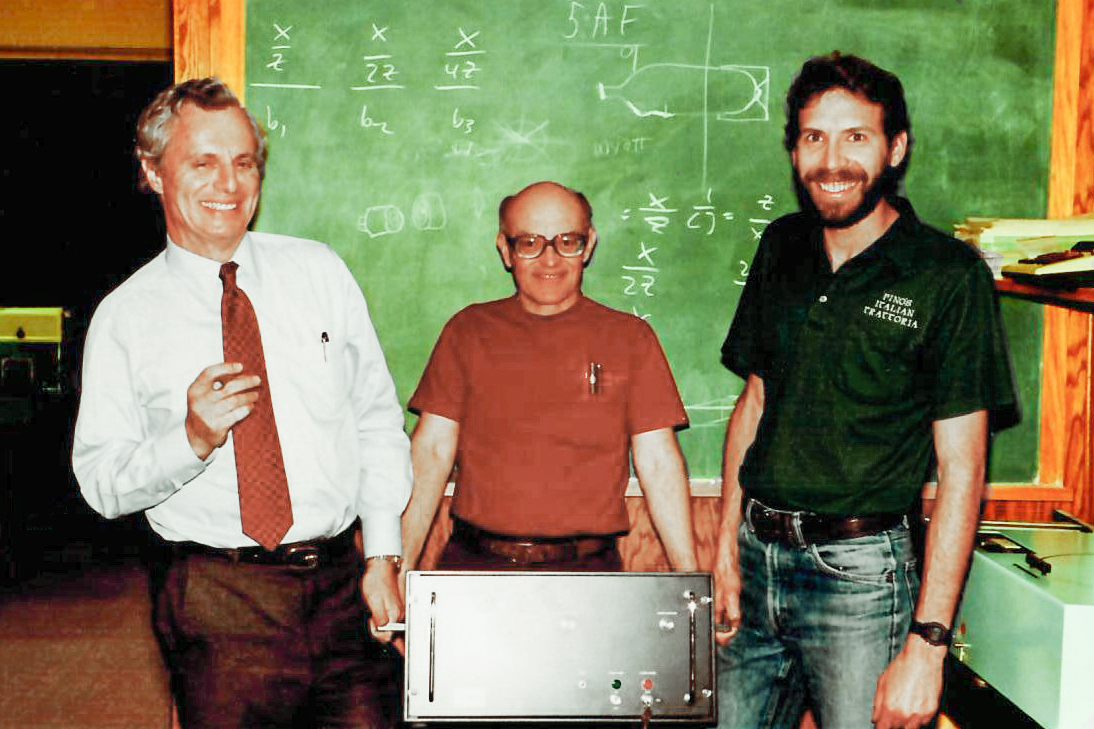

It’s hard to believe that Wyatt Technology began its improbable life forty years ago. Many of our employees and customers weren’t even born then! At the time, Dr. Philip Wyatt was a lecturer in Physics at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He had closed his first entrepreneurial venture, Science Spectrum, in the summer of 1981. But by a stroke of good—if delayed—luck, a proposal he had sent to the US Army in 1981 was awarded a contract in early 1982. And Wyatt Technology Corporation (WTC) was born.

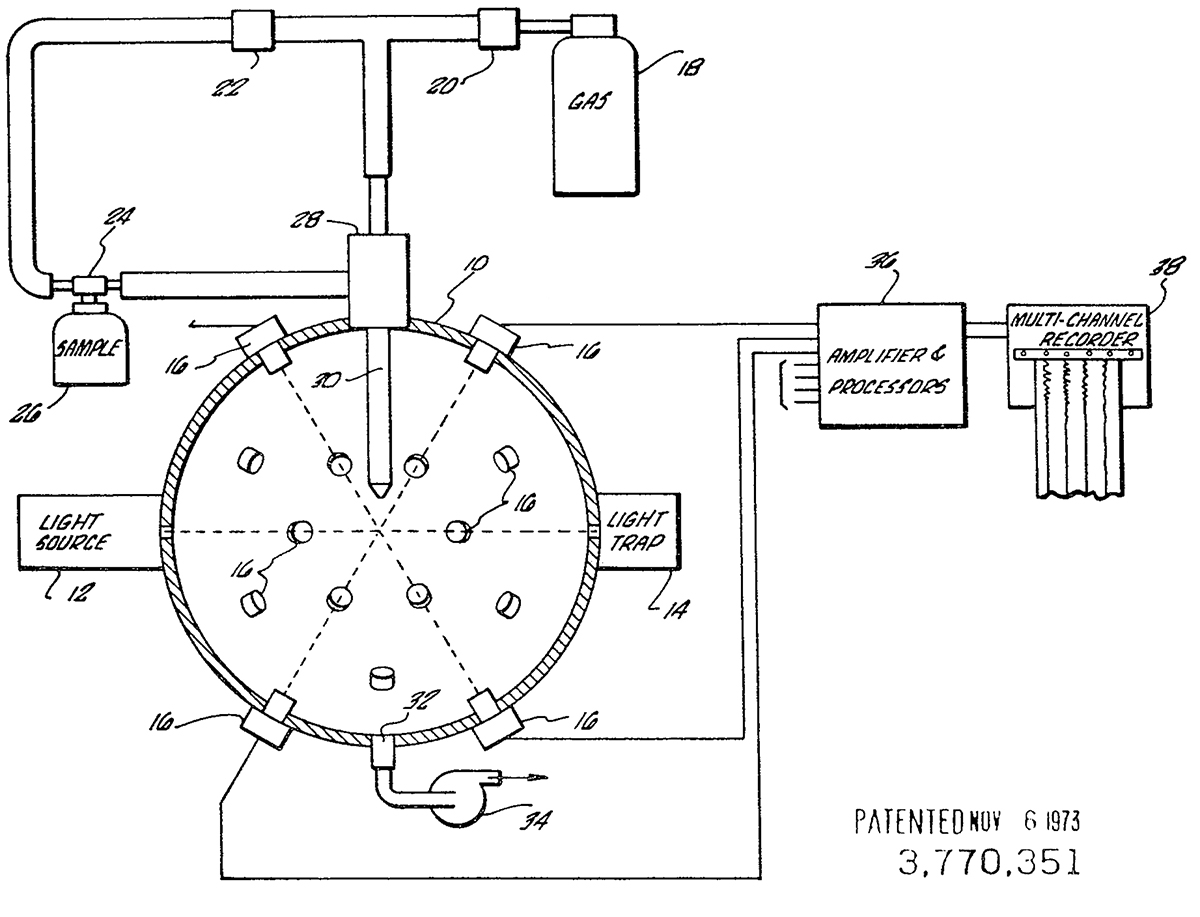

To say that its beginnings were modest understates the challenges that lay ahead. The Army was funding a $50,000 contract, but the money was not paid unless the work had been done. Progressive payment contracts work this way—but startups typically do not. Somehow, Dr. Wyatt (aka Dad and Phil) managed to resurrect a few instruments he had sitting in his garage, and began making the multi-angle light scattering measurements that would define the core of Wyatt Technology.

Dr. Wyatt’s work at Science Spectrum had established the company—and himself—as authorities of multi-angle light scattering instruments. To be sure, this was not necessarily saying a lot in 1981. Despite Science Spectrum’s groundbreaking use of early Intel microprocessor chips in its instruments, and the first commercial use of lasers in scientific instruments, light scattering was a little-known and seldom-used part of the analytical laboratories of the world. But, as the saying goes, you come into this world with a name and leave with a reputation, and by the early 1980’s Dr. Wyatt’s reputation was worldwide.

Dawn of the DAWN

Sometime in late 1982 or early 1983, Dr. Wyatt received a phone call from the Johnson Wax Company (the people who make floor waxes and polishes and a variety of other home-care consumer products). Johnson Wax wanted to know if Wyatt Technology (a company employing exactly one person) could build them a multi-angle laser light scattering instrument with flow through capabilities for chromatography applications. Bob Warner, the scientist at Johnson Wax, needed this detector for Hydrodynamic Chromatography (HDC). Phil Wyatt said he’d get back to them with a price and after a weekend spent consulting with an electrical engineering friend as well as a mechanical engineer who also ran a machine shop, Dr. Wyatt assembled a quotation, doubled the number, multiplied by Pi and presented it to Johnson Wax. The Racine, Wisconsin-based company accepted it almost immediately leaving Dr. Wyatt with the distinct impression that he could have and should have charged more!

By late 1983, three important things had happened to Wyatt Technology: Geof Wyatt, Phil’s oldest son, had been hired as full-time Employee #2, and the Johnson Wax instrument was ready to ship, and Phil had decided to name this first-born instrument DAWN. Now DAWN was not the name of an old girlfriend, or his wife, but in fact, an acronym for Dual Angle Weighted Nephelometry. And even though the DAWN for Johnson Wax had eight angles, Phil liked the name.

Geof wanted to know what Johnson Wax was going to do with its instrument, and Phil mentioned something about HDC, but encouraged Geof to contact Bob Warner and find out for himself.

Geof did, in fact, call Bob Warner, who explained that he was after a multi-angle light scattering detector for HDC, Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), and molecular weight determinations. The only detector available was a Low Angle Laser Light Scattering (LALLS) instrument sold by a company called Chromatix, but it was plagued by noise caused by the low angle of detection and the almost impossibility of getting solvents and samples clean enough to be able to distinguish one from the other.

Fruitful leads

While Geof understood almost nothing that Dr. Warner had told him, he wrote up a press release for a new product and sent it with a photograph of the instrument that had been shipped to Johnson Wax to scores of trade journals. What else was he supposed to do? Most of his time was spent helping his father make light scattering measurements of the bacterial response to toxicants, mutagens and metabolic poisons that the US Army contract had awarded the company.

This was late 1983 and early 1984, before the Internet had eradicated virtually all trade publications. In those days, trade journals published New Product Releases and had what were called reader service response cards (postage-paid, “Bingo” cards where the reader would circle the product number corresponding to the product(s) of interest). The magazine then printed out pre-addressed, gummed labels and sent them to each company whose product had been featured. The company, in turn, would send out product literature to the reader. This was the antithesis of instant gratification.

Phil and Geof were stunned when hundreds of leads poured into Wyatt Technology. There was just one small problem: Phil and Geof had nothing to send to the readers thirsting for more information on this DAWN Multi-angle Light scattering product! They had no brochure, they had no demonstration instrument, they had little idea what the instrument could do. So they employed some creative writing and finally produced a small, black-and-white brochure. With only the US Army $50,000 contract as income in those days, Wyatt Technology had virtually no financial resources available. Like so many things at the time, the brochures were produced on a shoestring budget, and envelope addressing, stuffing and even licking, were done by Phil and Geof.

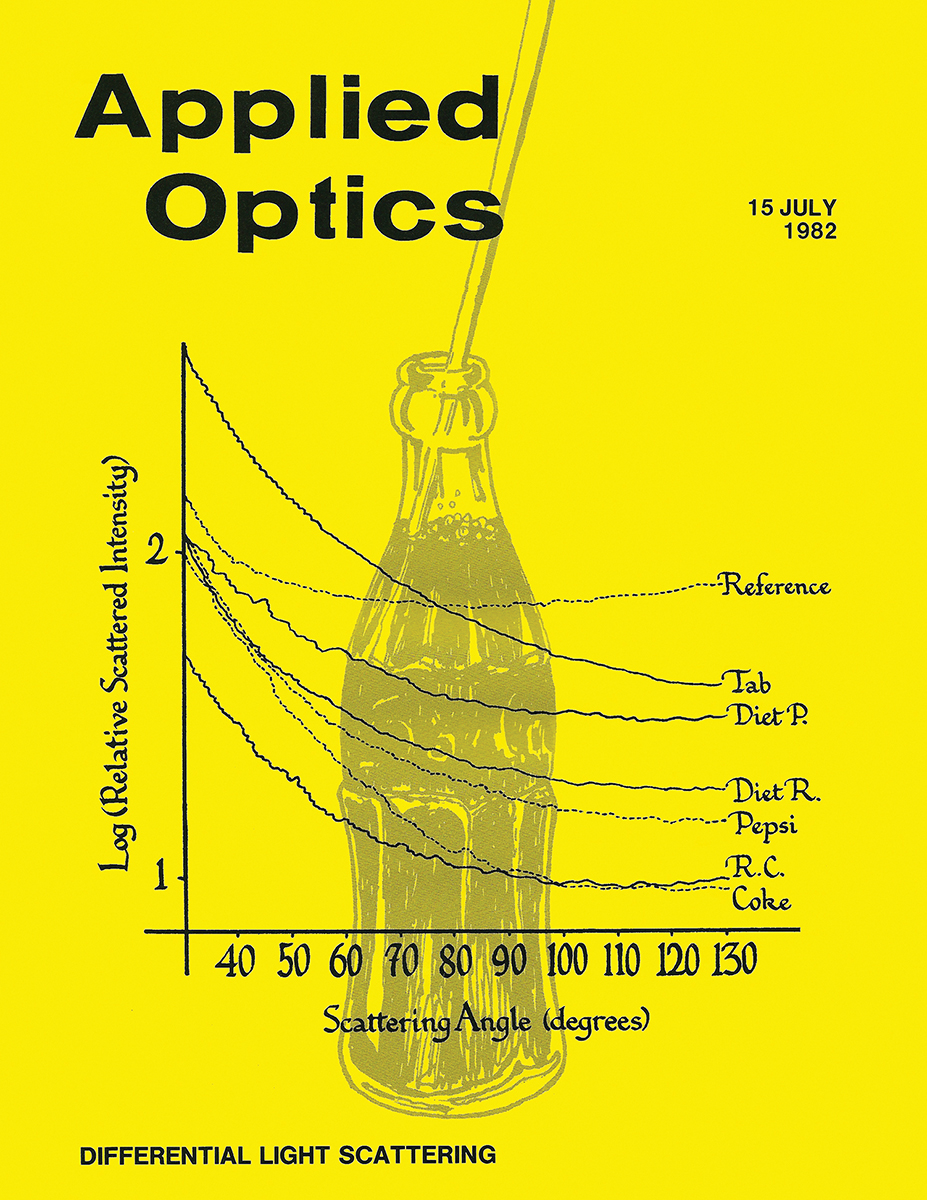

In early 1984, the Coca Cola Company become deeply interested in the multi-angle light scattering analyses of cola drink residues after discovering Phil Wyatt’s cover article for the 15 July 1982 issue of Applied Optics. Coca Cola was concerned that with our MALS technology that we might be able to deconstruct the magic formula for Coke that they call “7X.” The ensuing contracts with Coca Cola had little to do with their original formula and more to do with the kinds of things people put into their Coke bottles when they’re empty. It turned out that motor oil was one of the more popular liquids! The series of Coca Cola contracts that developed over the next couple of years bolstered the company’s precarious financial position, and even enabled us to hire a couple of people.

But a point of inflection for the company—although we didn’t know it at the time—came one afternoon in the Spring of 1984 when Mr. Joe Parli, from the AMOCO Production Company, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, called Wyatt Technology. Joe had read one of the New Product Releases and wanted to find out more about the DAWN. He explained to Geof that AMOCO had a Chromatix CMX-100 instrument, which was a Low Angle Laser Light (LALLS) scattering instrument. The extra “L” was added to the LALLS acronym (“low angle laser light scattering”) to symbolize “laser” reminding the user of the very narrow beam diameter facilitating small angle light scattering measurements.

The genesis for the Chromatix instruments had come from Dr. Wyatt’s previous company, Science Spectrum, in the 1970’s when Wilbur Kaye, of Beckman, had seen Science Spectrum’s laser-based instruments and concluded that microbiologists (to whom Science Spectrum was selling) would never be interested in something so sophisticated. Instead, he figured, analytical chemists were much bolder and willing to invest in advanced instrumentation. By 1974, Beckman Instruments had sold off its low angle laser light scattering (LALLS) device (introduced unsuccessfully in 1972) to Chromatix, which began further developments with measurements on GPC-separated polymer samples. Low angles are always noisier than higher angles, so making measurements at lower angles is always fraught with sample cleanliness issues. Still, purveyors of low angle instruments have come and gone over the intervening decades—each one proclaiming that you can change the laws of Physics!

Joe Parli was not at all happy about the noise that was overwhelming the signals he wanted to measure with his Chromatix. So he asked Geof, “You talk about multi-angles, what angles are they?” Geof said that just as with an air conditioner that has three settings: Low, Medium and High, so too, did the DAWN have low, medium and high angles. Joe asked for references and Geof pointed him in the direction of Bob Warner. In August 1984, Joe Parli placed an order for the second DAWN instrument. His application? Gel Permeation chromatography (GPC). In a short period of time Dr. Wyatt would refer to GPC as the acronym for Geof’s Pet Concept.

Rather than use the capillary-based flow system with seven angles of detection that Bob Warner’s instrument had, WTC delivered a new and improved system incorporating a cylindrical glass flow cell with 15 detectors spaced about it. This flow cell had almost mystical properties, or so claimed Dr. Wyatt, who discovered that the differences in refractive index between the solvent and the flow cell’s glass enabled measurements to be made at lower angles and higher angles than would have ordinarily been possible. Snell’s Law sometimes works in strange ways.

As DAWN instrument sales began to increase, ever-so-slowly, the government contracting business decreased. Wyatt Technology won notable Small Business Innovative Research grants from the Office of Naval Research (for a “laser troller”—effectively a multiangle light scattering instrument tethered to optical fibers more than a kilometer long), the NIH for looking at the effectiveness of AZT (an anti-AIDS drug), as well as follow-on funding from the Army that helped Wyatt Technology refine their instruments.

Hardware and software

While the first instruments came with RS-232 interfaces, and the first customers collected data and processed that data on minicomputers and the very first personal computers. But Wyatt Technology, with fewer than ten employees, had no software engineering and Phil and Geof frequently argued about the need for software. In 1985 the arguments reached a crescendo and Phil Wyatt banged his fist on his desk and declared “[Expletive deleted] if our customers are smart enough to buy our instruments they’re smart enough to write their own software!” Fortunately, the argument didn’t stop there, but in an ironic twist of fate, Wyatt’s first software programmer was none other than Philip Wyatt himself! And as a Physicist, he programmed in his preferred language: FORTRAN. Thus great oaks from little acorns grow.

Until about 1986 Wyatt Technology’s instruments were either DAWN F (F for Flow-through) or DAWN Model B (Batch mode light scattering measurements of samples in scintillation vials). There were no other products the company made. Joe Parli, from AMOCO, had found an interferometric refractometer made by a company called Tecator, in Sweden, that had been primarily used for Brix values, but that he was using for dn/dc determinations. This refractive index instrument had the ability to be built at a variety of wavelengths, thanks to its optical interference filters. Tecator called this instrument the Optilab, and it was not a simple instrument to build…as Wyatt Technology would soon find out.

A roommate of Geof’s from college had encouraged him to apply to Harvard Business School, since Harvard had had more than its share of investment bankers and management consultants. Instead, it now sought people who came from real manufacturing companies. And by temporarily doing away with the GMAT exam, they hoped to appeal to people who weren’t superlative at test-taking. Geof took the bait, applied, was accepted and off to Boston he went in the Fall of 1987.

Having Geof out of the office gave Phil some breathing room. Within a year he had inked a deal with Tecator to purchase the Optilab product line for $100,000. This was Wyatt Technology’s very first corporate acquisition, and although no one knew it at the time, it set the pattern of acquisitions that were to follow. Among the many discoveries that Wyatt Technology made with the acquisition of the Optilab product line was the fact that there were no drawings for the parts. There was barely a Bill of Materials. And the few parts that had any description were in Swedish, which was not one of the languages that Dr. Wyatt spoke. Fortunately, as part of the purchase, Tecator loaned one of their technicians to Wyatt Technology to transfer the product. Ultimately, the parts were documented—in English—and a complete Bill of Materials was created. The company even began to sell Optilabs, painted “Wyatt blue” built for 488 nm wavelength, the same wavelength as Argon-ion lasers.

Those are a few of the early tales of Wyatt Technology's modest start. We want to thank our many customers and staff for helping us continue the process of bringing 40 years of technical innovation to market and making Wyatt Technology the company it is today - the recognized leader in instrumentation for determining the absolute molar mass, size, charge and interactions of macromolecules and nanoparticles in solution.

Stay tuned for Part 2 which dives into the technological evolution of light scattering!